I talk with Kim Winter, editor at the Basketmakers Association, about my practice.

KW: How did you get into making baskets with foraged materials?

The training I had at degree level (3D Craft, Brighton Uni) was formative, being materials led. I remember in the first year going into the metals workshop, being shown tools and materials and, without any teaching/technical input (other than essential H&S), having a week to experiment and play. We had the same immersion in all the workshops, and this kind of approach became embedded in my practice, leading naturally to a curiosity about using foraged materials.

In my early 30s I took time out of my job (teaching art and design to 12-18 year olds) because of ill health, and went to live for a year in rural Devon as part of a land-based retreat community. I spent a lot of time wandering the landscape observing things, making small pieces and installations from found objects and plant materials. This period enriched my sense of connection to the natural world and expanded my plant knowledge.

Later I joined a team of archaeologists in Sussex, doing experimental archaeology and teaching ancient crafts and technologies. A small organisation training people for work in the heritage sector, it received government funding (now disbanded because of cuts). Our projects were based on archaeological evidence of pre-Roman times, using a broad range of materials and techniques: copper smelting; green woodworking; wild foods; natural dyeing; coracle-making; natural hide tanning; early pottery; reconstructing buildings; early textiles; flint knapping.

I began to appreciate how weaving technology shaped us as humans; over millennia we’ve been dependent on basketry techniques: our homes, boats, nets, clothes, baskets.

All the crafts involved sourcing raw materials, and the buildings were especially interesting to me, particularly those we built based on evidence from the Stone Age. We basically wove giant upside-down baskets from hazel and ash, sunk them into the ground, thatched them with reeds or straw and sometimes in-filled the woven walls with clay or crushed chalk. I began to appreciate how weaving technology shaped us as humans; over millennia we’ve been dependent on basketry techniques: our homes, boats, nets, clothes, baskets.

I learned about making string and netting from tree bast (inner bark), as found with ‘Otzi’, the natural mummy of a man from around 3350BC. I learned to weave with brambles and hazel, rushes and reeds, grasses and bark. I researched various relevant archaeological finds including European wetlands, Durrington, Must Farm, Whitehorse Hill, and visited ethnographic collections and museums. I began to appreciate how the traditional basketry of any community is wedded to place and the plants that grow there; how making techniques emerged from the properties of those plants, and how universal and ancient those techniques are. The same ones we still use today.

It made me think a lot about the provenance of materials and impact of sourcing them; I wanted to have a light footprint. Ever since college I’d felt uncomfortable about adding more stuff to the world. I saw how little remained from the basketry structures of our ancestors- naturally returning to the earth- and I wanted my own makings to do the same. By connecting to an ancient lineage of knowledge I reconnected with the fundamental human drive to make, my own fundamental drive. It was like going back to the source, understanding the ingenuity of distant ancestors whose brains and hands were pretty much the same as ours today.

KW: what is your favourite foraged material to work with?

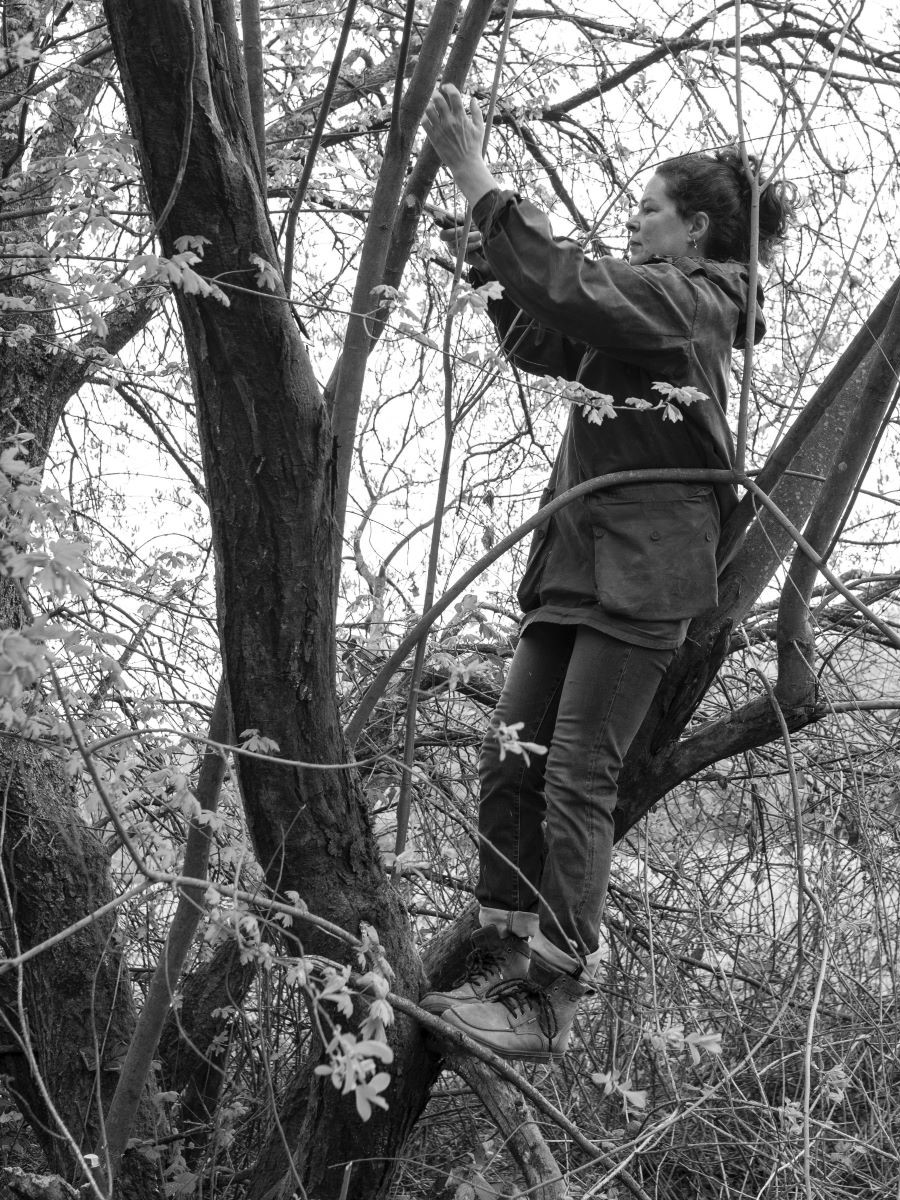

I honestly don’t have one. I’m a generalist rather than a specialist. The challenge of discovering how to work with each one interests me. It takes a long time to understand how a material handles and to feel confident with it. Harvesting from the wild is variable: plants differ depending on the growing season and how they’ve been managed.

KW: What is your favourite make and why?

In recent years I’ve made large-scale works at Wakehurst (Kew), site specific sculptural pieces. The briefs have all been very open: a response to the plants and the place. Most recently I created Hazel Holloway; prior to that I made a large, netted structure from 70 metres of meadow grass, and also a 7 metre high archway in the woods from coppiced hazel. A common theme is contained space, much like the baskets and wild clay vessels that I make are. I love working large scale in that way.

Mesolithic style dwelling, Sussex

Hazel Holloway, Wakehurst

I do a lot of teaching, mainly in the woods in Sussex (also at heritage sites/museums). It’s an opportunity for people to learn a technical skill, going home with a basket, alongside the less tangible experiences of connecting to the land and the more than human community, feeling part of an ancient lineage of people coming together to harvest and make, having the benefits of slowing down from busy lives.

It’s empowering to learn how to gather your own raw materials from the landscape and create a functional, tactile, beautiful object. Learning how to make fire, eating soup cooked on that fire, drinking tea made from plants we’ve foraged, the simplicity of sitting and making together in a circle with no phones/wifi, the sounds of birds and breeze in the trees… all this can be equally meaningful. It’s satisfying to offer these experiences and see the results, hearing from people later about the impact of their time in the woods.

There’s a tremendous amount that goes into making woodland courses run smoothly, lots of practical logistics. I’m always grateful for the support of the family farm whose woodland I use. The weather’s an extra factor, sometimes unpredictable. I aim to have as little infrastructure in the woods as possible so that we feel away from everything and can immerse ourselves, while also being comfortable.

There’s an intangible experience of connecting to the land and the more than human community, feeling part of an ancient lineage of people coming together to harvest and make .

I have two workspaces: in the woods I forage and process materials, and also do wild pot firings. Sometimes I stay overnight, which is the best. I always feel like I’ve had a re-set after being there doing my thing. Most of the making is done in my studio, a converted shed at the bottom of the garden at home.

KW: Can you share a making tip with us?

If it’s long and pliable it’s definitely worth experimenting with. To avoid shrinkage you want to use the material either when it’s partially dried, or dry it out completely and then re-dampen it. Remember to harvest honourably: an indigenous tradition of giving thanks (you can read about it in ‘Braiding Sweetgrass’ by Robin Wall-Kimmerer).

Watch a 3 minute film about my practice.

A version of this post was originally published in the Basketmakers Association newsletter no. 180, Feb 2022. Anyone who’s interested in baskets may join the association and receive the newsletter directly, as well as have access to other useful and inspiring resources.

May all the plants we rely on for basketmaking thrive in the years to come for future generations of makers.