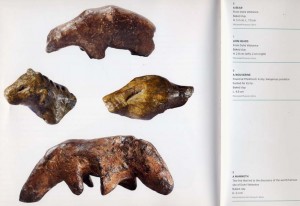

At the 2013 Ice Age Art exhibition at the British Museum I spent some time studying the baked clay animals in the show. They’re mostly small fragments, around 2-4cm in size. Despite their smallness and lack of detail they’re exquisite and the essence of the animals is palpable.

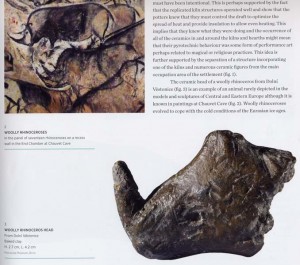

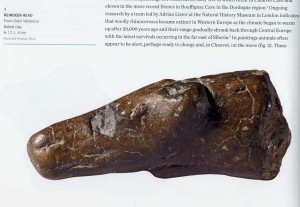

Wooly rhinocerous head from Dolni Vestonice, H2.7, L4.2cm.

What really got my interest was that in the accompanying text it described how scanning with electron microscopes had revealed that the clay animals had been put into their firing in a wet state. It suggested this had been done with the intention of them breaking in the fire, which is indeed what happened. Breakage happens when trapped water in the body of the clay expands rapidly in the heat of the firing.

Usually potters dry their work slowly to ensure it’s completely dry before firing to avoid this happening. However, according to Tristan Bareham, archaeologist and potter, it is in fact possible to fire wet clay objects without breakage. He told me about successful experiments he’s done putting wet pieces into an open firing, saying that the key is for them to be either fully wet or fully dry when put in (so long as there are high levels of temper included). It’s partial dryness that causes the problems as it reduces the porosity of the clay body and thus the ability of the water vapours to escape. Anyone who works with clay knows that the reality (especially when working with raw clay and open firings, as I do) is that you can never be sure if the piece will come out of the whole process intact. ‘Wet’ firing sounds counter-intuitive but intriguing so I’ll be giving that a try.

Experiments carried out by Vandiver and Soffer, and cited in chapter 5 of the British Museum’s accompanying book to the Ice Age Art exhibition (from which the images on this page come) were around the making of these small clay animals. From these experiments and from looking at other ceramic finds at Dolni Vestonice and the level of technical competence in the firings themselves, they surmise that these breakages are most likely intentional and were caused by the items being wet in parts when fired. It’s evident from other examples that the makers clearly knew how to conduct ‘successful’ firings, so they suggest the intention for these items was for them to break in the process. We can never know what the makers thought or intended, but Vandiver and Soffer suggest ceremonial, or performance aspects to this proactive destruction of what’s been created.

There are also beautiful carvings in the exhibition which are broken; analysis of the marks indicates that this was done deliberately too. We can only speculate about these breakages, whether they were ritualistic, revengeful, catharsis or something else.

Around the time of going to see the British Museum exhibition I was making a clay vessel that I wanted to use symbolically to deal with the death of my brother. I had the idea to make it, use it on a fire and then break it as a kind of release. It was really interesting to make it knowing that I would most probably end up intentionally breaking it. Making the pot, the first attempt had to be abandoned and the clay squashed up again- my focus had wandered in the making and the form had gone wonky. Was I going to make a shoddy piece because of its destiny, or was I going to give it the creative energy I’d give to anything else I made? I wanted to imbue the vessel with the issues that needed releasing… and that required a good deal of sustained focus during the slow, methodical hand-building technique I like to use.

The pot came out of the clamp kiln firing in one piece and so some time later I went to the woods to do the final stage, the breaking. Having lit a cooking fire beneath the vessel and boiled some herbs and water in the pot, I turned it over onto the embers, bottom up. It was a challenging thing to do, to break this pot I’d made and invested energy into. But with the symbolic aim in mind it was a powerful action: one swift, focused blow from a hammer.

I was reminded of the story of the Buddhist monk who, when challenged by a student for possessing a beautiful glass object, replied that every time he gazed on it he imagined it broken. It was a way of practising non-attachment.

I also reflected on the place of destruction in the creative process in general. I believe it’s integral. Like the inevitability of winter, decay and breaking down are necessary… just as composting is essential. It’s a kind of release. I remembered hearing about Bronze Age burials with clay pots in them that have had a hole made in the base. Innumerable artists throughout time have explored this theme, indeed continue to explore and express it.

You can learn how to make pottery on a Native Hands Wild Pottery course, where we dig our clay from the site and fire out pots in an open fire.