Last winter there were a few weeks when it was unusually snowy. And in the usual English way, human life pretty much ground to a halt because of it. One morning I heard a loud thump at a window. At head height was a little clump of small downy feathers stuck to the outside of the glass. My eye caught a movement in the undergrowth of the flower bed and I saw it was a fallen mistle thrush.

Last winter there were a few weeks when it was unusually snowy. And in the usual English way, human life pretty much ground to a halt because of it. One morning I heard a loud thump at a window. At head height was a little clump of small downy feathers stuck to the outside of the glass. My eye caught a movement in the undergrowth of the flower bed and I saw it was a fallen mistle thrush.

Then a male sparrow hawk appeared and stood on the snow nearby, eyeing up the situation. I froze. He was incredibly beautiful. I’d never seen one up close before- usually they’re whizzing by, through the trees. His yellow eyes were so bright and beady, his plumage exquisite- much more stunning than in the photo below, especially against the snow.

He came and got the thrush, carried it out onto the snow, less than two metres from the window, and pecked at its breast, removing the feathers, until he’d extracted and eaten the main organs. He perched in a nearby bush to clean his talons and after a few minutes flew off. His hunger must have driven him into town in search of food… and I gather he would have killed the thrush by flying into it so it got knocked out against the window. It was interesting that he ate only the main organs- I imagined he’d have eaten the flesh too… but I assume in that cold weather it made sense to just go for the highest energy-giving parts.

It was awe-inspiring and I wanted to honour the thrush. They’re one of my favourite garden birds, I listen out for their song from the nearby ash trees, and I was sad for its death… but it was also wondrous to see the power and beauty of the sparrow hawk.

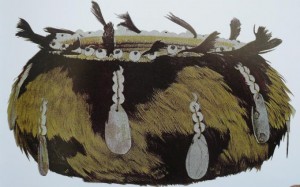

For ages I’d been thinking about making a basket with feathers attached, after seeing a photo of one (below) in Bryan Sentance’s wonderful book: Basketry, a World Guide to Traditional Techniques. So I made my basket, coiled from grass grown in my garden, using hemp twine, and I sewed on the flight feathers from the thrush, which I’d taken before tucking the bird’s body into a sheltered spot in the undergrowth.

‘Gift’ or ‘jewel’ baskets, covered with feathers, are a speciality of the Californian Pomo. The baskets’ most important function was their destruction in honour of the dead.

I had the feeling to make my basket an ancestral offering, so I kept this and the birds in mind as I stitched the basket quietly by the fire. I really liked the mouth of the basket, the way it framed the space within. In fact I liked it so much I didn’t want to give it away… but it seems to me that to give away something you really love is a powerful thing, it’s what gifting is all about. So I went alone to some favourite woods: a beautiful, undisturbed ancient hazel coppice, put the basket inside a mossy hollow in the trunk of a very old hazel, on the edge of the woods, and left it there.

It’s only now, as I’m writing this, that I realise that’s in line with what the Pomo did with their feathered baskets- at the time I didn’t make that connection, but it seems entirely right for the mistle thrush.

You can learn how to make baskets from foraged materials, including grass, on Wild Basketry Courses with Native Hands