Bare feet and windrows.

I’m at Wakehurst, in Bloomers Valley, checking out the plants in this meadow for my Meadow Weave residency. It’s a species-rich conservation-grade meadow, the result of a big restoration project here. I’m admiring the dramatic entrance to the valley, and I have a special love of meadows surrounded by mature trees, of the stillness that’s created within generic prozac.

I’m at Wakehurst, in Bloomers Valley, checking out the plants in this meadow for my Meadow Weave residency. It’s a species-rich conservation-grade meadow, the result of a big restoration project here. I’m admiring the dramatic entrance to the valley, and I have a special love of meadows surrounded by mature trees, of the stillness that’s created within generic prozac.

Among the plants here are common knapweed, autumn hawkbit, birds-foot trefoil, ox eye daisy, dyers greenweed, red clover, meadow vetchling, ragged robin, devils-bit scabious and common bettony. Descriptive and intriguing names. The yellow rattle is already setting seed (and rattling), the ox eye daisies and ragged robin are in full flow, and the knapweed looks like it’ll be an amazing sight in a couple of weeks, when it comes into flower.

It’s so peaceful here this morning, just birdsong, insect sounds and an occasional ‘plane from Gatwick overhead. Despite the bright, warm sunshine, the grass is still fresh with dew… I have to go barefoot. Scroll down for a clip of this.

At the back end of Wakehurst, the farm hay has just been cut. Iain Parkinson, conservation and woodlands manager, has arranged for it to be cut long, which is optimal for my purposes. And he’s kindly laid a large pile of it out on the ground, in the sun, next to my temporary studio: the barn on the right in the picture above. The barn’s a wind-tunnel… but I like being here in an agricultural setting. It reminds me of the family farm and I feel at home.

I sort and turn the hay until I have a couple of nice windrows of my own. Left unturned too long it quickly starts degenerating into compost. This hay is made up of a rich variety of grasses: I can identify fescue, rye-grass, Yorkshire fog, sweet vernal and cock’s-foot… but I think there are others in the mix too. It’s the sweet vernal grass that makes the hay so fragrant.

I sort and turn the hay until I have a couple of nice windrows of my own. Left unturned too long it quickly starts degenerating into compost. This hay is made up of a rich variety of grasses: I can identify fescue, rye-grass, Yorkshire fog, sweet vernal and cock’s-foot… but I think there are others in the mix too. It’s the sweet vernal grass that makes the hay so fragrant.

Traditionally hay making was a crucial part of the year. As a vital source of fodder over winter for the farm animals, it was a highly valuable crop. I’ve heard it said that the way to hurt a farmer most was to burn down a hayrick. A rick can spontaneously combust too, if the hay is stacked when it’s too green; so much heat is generated by the decomposing process.

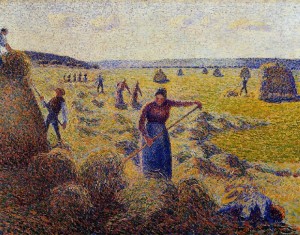

Camille Pissarro 1887

When to cut the hay is a question of fine-timing: a good stretch of warm dry weather’s needed to allow time for the hay to dry in the fields and be turned a few times before it can be stored. Back in the day (before baling was developed) ricks had to be made, a tricky job. Consequently many hands were traditionally needed at this time and the community all came together to bring in the hay harvest: a truly communal activity.

The work I’m making here at Wakehurst is intended to symbolise this binding of communities through the activity of hay making, as well as celebrating the material itself.

The current Meadow Folk Exhibition at Wakehurst highlights a contemporary hay/meadow community of researchers, conservationists, field workers, land managers, botanists and others, celebrated as part of Wakehurst’s Meadows Festival this summer.

Here’s a short video showing me exploring the meadow plants down in the beautiful Bloomers Valley: